In Search of Billiken’s Roots – The People Behind the Throne

How does a newly patented God inspire a global cult in a few short months? On the surface anyway, the story of Billiken reads like a fairy tale of good luck and success. Designed by a Kansas City art teacher and illustrator named Florence Pretz, Billiken rapidly became a worldwide phenomenon. Long before the internet, Billiken was a viral meme, his smiling face appearing on everything from dolls to postcards to jewelry. Within weeks, displays of Billiken statues lined the windows of bookstores and stationers, followed closely by Billiken banks and dolls in toy stores and department stores around the country, and soon around the world. Of course, the reason for his popularity was not his looks alone; it was also his philosophy and what he represented. He was, and still is, the God of Happiness, the God of Luck, The God Of Things As They Ought To Be. But exactly how Billiken achieved this amazing popularity, and who was responsible for it, has never been explained until now.

The published facts available to date are sketchy and derived mostly from the artifacts themselves. It is known that Billiken’s first appearance was as a plaster or “chalkware” figure. The plaster figures have a small metal medallion or coin inset into the plaster that gives some clues about the early days of the Billiken craze. The earliest versions read “The Craftsman’s Guild, Highland Park, Ill”. Subsequent versions were a very similar design marked “The Billiken Company Chicago”. Both of these designs state “Copyright” and “trademarked”, but do not mention the patent.

A third version of the medallion also exists; a more ornate design that credits both “The Craftsman’s Guild” and “The Billiken Company”. This design also indicates that the Billiken patent had been granted, stating “Reg. U.S. Pat. Off” and gives the patent date.

The questions remain: Who was Florence Pretz? Who was The Craftsman’s Guild? And who were the people in The Billiken Company? This article finally reveals for the first time, an inside look at the people behind the Throne – Billiken’s Mother, his Father and his Dutch Uncles.

Billiken’s Mother – Florence Pretz and the Birth of Billiken. Is Billiken really Canadian?

It is known that Billiken was first given life by his mother, Florence Pretz of Kansas City, as she held the design patent granted on Oct. 6, 1908 that shows the drawing of Billiken (although he is simply called “a statue”). The patent was applied for on June 12, 1908, but Billiken was already well known by then in the USA

and even before that in Canada.

Billiken’s first known public appearances were in a Canadian magazine called The Canada West, A Magazine of the Sunset Provinces in 1907. This journal was published in Winnipeg, edited by Herbert Vanderhoof and published by Vanderhoof-Gunn. It was succeed in 1910 by another Vanderhoof publication called The Canada Monthly.

Between May 1907 and January 1908, Billiken appeared in five Canada West stories. These were all written by Sara Hamilton Birchall and illustrated by Florence Pretz. These two were friends, both originally from Kansas City

they moved to Chicago, and may have been roommates at about this time. The text of these stories can be seen on the Billiken Stories page, and include such titles as While Billiken Slept[1], Billiken’s Umbrella[2] and Billiken in the Nasturtium Vine[3].

Birchall takes her inspiration for these stories from Canadian poet Bliss Carman’s poem Mr. Moon, A Song of the Little People which appears in the 1896 book More Songs from Vagabondia. In fact, one of the 1907 Billiken stories, Mr. Cricket and His Flute[4], is about another character from Carman’s poem and even quotes the refrain of Mr. Moon. When combined with statements made by Miss Pretz, this leaves no doubt as to the origin of Billiken’s name. Whether it was given to him first by Florence Pretz, or if the name came as a result of illustrating Birchall’s stories, the source of the name was Bliss Carman’s poem. You can see these stories on the Original Billiken page.

Billiken was about to lose his wings however, and metamorphose from a tiny, child-like Canadian fairy into a powerful God – the God Of Things As They Ought To Be. In the process he gained a US patent, financial backers and a throne; but he never lost his impish grin.

Billiken’s dramatic United States debut was a full page in the Chicago Daily Tribune on May 3, 1908. The article featured two photographs of Miss Pretz, one a lovely portrait and the other showing her dressed in a kimono “burning incense before her idol” the Billiken:

A quarter of the page is taken up by a large drawing of the Billiken, who was soon to take the city by storm. Other illustrations in a Japanese theme accompany the article and cement the notion of Billiken’s Asian heritage. These illustrations bear the copyright of Atkinson, Mentzer & Grover (remember that name). The article begins:

“Someday you will see the queer idol whose picture appears on this page, grinning at you from the top of an office desk, or from some altar in your friend’s den, or from the window of an Arts and Crafts shop. You may or may not see his creator, Miss Florence Pretz, a young Chicago artist, but her history is tied up with that of the god Billiken in a way that proves his claim to being a mascot. And, what is stranger, whenever the friends of Miss Pretz look at him and then look at her they declare there is a hint of family resemblance in the smile and they wonder if there is some strange, faraway kinship between them, in spirit at least.

‘He is the god of things as they ought to be’ said Miss Pretz as she set him up for her best girl friend to look at him after molding him out of clay and having him cast in plaster. ‘There, smile for the lady, Billy’. Then the two friends began burning incense before him and worshipping him, and it was not long before he began to prove his credentials as a mascot by bringing them good luck.

First, the friend came to Chicago as a stenographer, bringing a plaster edition of Billy with her and setting him up in her own little bachelor girl flat. The next thing she knew, her small book of poems, which she had been writing and dreaming in girl fashion, found a publisher – you may know it – it is called the ‘Book of the Singing Winds’. Then, seeing her own good luck, she had the courage to take the copy of her friend’s little god Billiken forth to publishers, artists and other formidable people –anybody who would launch him in Chicago.”

The article continues on about how Miss Pretz had been dreaming of “things Japanese” and drawing “Japanese sketches” since she was a young girl, even speculating that she must have been Japanese in a former life. This all serves to make it clear that the inspiration for Billiken was drawn from the mysterious Orient.

The article goes on to describe how plaster Billikens were now being produced by the hundreds and sold at the arts and crafts shop, at the candy shop and at the art shop, and how this allowed “Tinker Bell” (as she was supposedly nicknamed) Pretz the opportunity to come to Chicago and work with her friend in a little studio in Highland Park. The article ends by saying: “the two friends burned incense before Billiken at night, never omitting the process, with the results that orders began to come in for their drawings. “He was the original official luck bringer of us all’ said ‘the friend’ who first started the god going in Chicago.”[5]

The friend mentioned in the article was, of course, Sara Hamilton Birchall, the author of the Billiken stories that had been appearing in The Canada West magazine. Birchall was not only a poet, but a lyricist and later one of the early women in the advertising industry with Kenyon & Eckhardt. It is likely some of the early Billiken verses were composed by Birchall. As a brilliant piece of public relations, the Tribune launch article definitely cemented the link between Billiken and sales and marketing from the very beginning.

In the July 1908 issue of The Canada West, an editorialby Herbert Vanderhoof noted the instant popularity Billiken was enjoying in the States. He wrote: “Billiken and Canada West readers are old friends. For more than a year the little gnome with his infectious grin has been a welcome guest in thousands of Canadian homes. It was in this magazine, and to Canadian readers, that he made his first public appearance, but he existed even before that as a little plaster cast in the possession of his creator, Florence Pretz, the artist.

Now in the States he has become the idol of the hour. Newspapers have taken him up, and the public generally are buying him right and left… our gnome has become public property, the present day craze. But we have a feeling of proprietorship in him because we knew him first. Sara Hamilton Birchall, poet and author, had told us all about him, and had explained his queer capers. With Miss Birchall as guide, did we not peer down his hollow log, and peep under grass blades to find him in his native haunts long before the Americans ever heard of him? Surely. And we, too, smiled with Billiken, because we could not help it.”[6] Several of the Canada West stories about Miss Pretz can be seen on the Florence Pretz page.

A later article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch gives more insight into the thought behind the creation of Billiken as well as confirms the source of his name. Miss Pretz says her intent was to “make an image of hope and happiness to sort of live up to”. She claims she even wrote a verse from The Rubiyat by Omar Khayam on paper, folded it up and placed it in the belly of the first clay statue she made. She says the verse was this one:

Ah, Love, could thou and I with Fate conspire,

To grasp this sorry Scheme of Things entire,

Would we not shatter it to bits – and then

Re-mold it nearer to the Heart’s Desire.

She then goes on to say that she got the name Billiken from a poem called Mr. Moon by Bliss Carman.[7]

Another account of Billiken’s creation appeared in the Chicago Daily Tribune in an article that announces the wedding of Florence Pretz to Robert A. Smalley, a Lincoln NE motor car dealer – on Valentine’s Day 1912. According to the article, Miss Pretz was formerly an art teacher at the Manual Training High School in Kansas City who “got the inspiration for Billiken in 1896 while looking at a collection of grouchy looking gods belonging to Miss Floy Campbell of the art department at the school. They brought to Miss Pretz’s mind the idea of fashioning a god who would smile and bring to his worshippers cheer instead of gloom.”[8]

Billiken’s Father and Family – Edwin Osgood Grover and The Craftsman’s Guild

Of course, to become a major commercial product Billiken needed marketing muscle and sales know-how. In the early days that was provided by Edwin O. Grover, who had a remarkable career as a salesman, editor, publisher and professor. He was also the founder of the Craftsman’s Guild of Highland Park and Boston, a loose cooperative of artists, writers and craftsmen. The Guild was part of the American Arts and Crafts movement, and produced “educational” children’s toys, beautiful limited edition books, furniture and other items –including Billiken.

Edwin O. Grover began his career with Ginn & Co., a textbook publisher, as a sales representative in the Midwest. There is no documentation to support the notion, but perhaps he met a young Florence Pretz, who was teaching in Kansas City during those years. After spending a few years learning the art of selling, Grover was promoted to editorial assistant at Ginn’s office in Boston. This was followed by a move to Rand McNally in Chicago, where Grover quickly worked his way up to chief editor of books.

In 1906 Grover associated himself with the publishing form Atkinson and Mentzer, which became Atkinson, Mentzer & Grover, with offices in Chicago and Boston. This company published text books, yearbooks of industrial arts and even made a foray into art supplies, developing a crayon to compete with Crayola. He went on to become the President of The Prang Company, a printing, publishing and educational art supply company, (remember those black tins of watercolors?) for several years before entering academia as Rollins College’s first Professor of Books.[9]

He served on the faculty at Rollins in Winter Park, Florida for over 20 years. Undoubtedly he was acquainted with patron and collector of Arts and Crafts Charles Hosmer Morse. Morse was a Chicago industrialist who built up the Fairbanks-Morse Company and was a founder of Winter Park as well as Rollins College. Mr. Morse’s collection forms the basis for the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park where one can view several copper pieces produced by The Craftsman’s Guild and donated to the museum by Frances Grover, Edwin’s daughter.[10]

Grover had a reputation as an enabler of the best kind. He provided encouragement, inspiration, direction and leadership to many associates and students over the years. For example, while at Rand McNally he published The Sunbonnet Babies, a successful reading primer authored by his sister and Craftsman’s Guild member Eulalie Osgood Grover. This became a standard text in the US for teaching reading. Or once, while having dinner at the house of his friend and Guild member Lucy Fitch Perkins, Grover noticed some drawings she had made. With his encouragement, and publishing connections, Perkins went on to create the beloved Twins of the World Series whose twenty six volumes introduced children of the early 20th Century to cultures and customs from around the world.

Of course a major part of Billiken’s charm has always been the Billiken Philosophy. The poems and sayings that accompanied Billiken set him apart from other charm dolls and mascots of the era. If there is any doubt in Grover’s role with regard to Billiken just consider the titles of the books he authored and edited during the Billiken years. The titles alone are enough to establish his paternity, the mark of the father upon the son: I Wish You Joy (1908), Just Being Happy -A Little Book of Happy Thoughts (1912), The Book of Good Cheer- A Little Book of Cheery Thoughts (1909), The Book of Courage – A Little Book of Brave Thoughts (1916), From Friend to Friend – A Partnership of Friendship (1916), and many more.

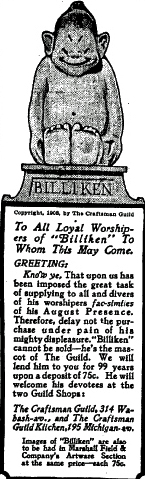

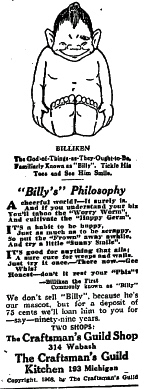

In May of 1908 the first advertisements for Billiken began to appear in the Chicago Daily Tribune. The launch advertisement noted that Billiken was the Guild mascot, available at the two Guild shops: The Craftsman’ Guild Shop on Wabash Ave. and The Craftsman’s Guild Kitchen on Michigan Ave. as well as at Marshall Field & Co. in the Artware Section. The price was 75 cents.[11] The second advertisement included some of “Billy’s Philosophy” and this combination proved to be a winning ticket. Billiken the phenomenon was born.

It was likely Grover who added copyright notices everywhere Billiken appeared, and perhaps he encouraged Miss Pretz to apply for her first and only patent. But Grover had full time responsibilities in publishing in addition to encouraging young artists like Florence Pretz and producing and selling novelty items, and Billiken was growing far too quickly to be a part-time enterprise. So in the fall of 1908, just months after Billiken’s arrival in Chicago, Billiken found himself at the center of a new corporation.

The Dutch Uncles – The Billiken Company

The Billiken Company was incorporated with $60,000 worth of capital stock in the State of Illinois on Sept. 24, 1908[12] by three men: Charles P. Monash, Toby Rubovits and James Rosenthal.[13] Their purpose was maximum commercial exploitation of the image of Billiken, a mission they undertook with zeal. Over its short, spectacularly successful history the company was also involved in several lawsuits and perhaps even ended up exploiting Billiken’s own creator.

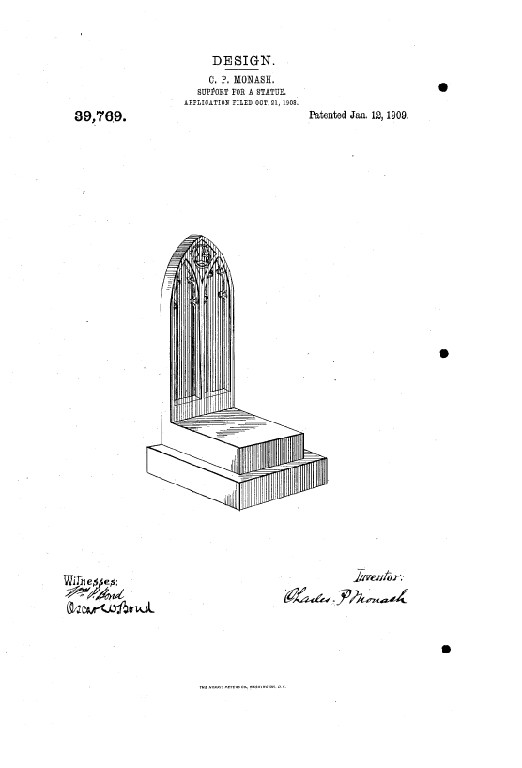

The first of the three owners, Charles Pincus Monash was a local businessman who had a company that made steam valves, like the sort of device used on the end of a radiator. The company he founded, Monash-Younker Company, is still in business in Elburn, IL. Other than providing capital and knowledge of manufacturing, Charles Monash knew the value of patents. In fact, he is credited with inventing a design for the support of a statue, the subject of US Patent 39,769, applied for on October 21, 1908 and granted on January 12, 1909. That design became the Billiken Throne. The Throne was one of the key accessories that helped popularity of the plaster statuette. Finally Billiken had a fitting place to sit as he was worshipped by the faithful. An image of the patent for the Billiken Throne is pictured here:

The second investor, Toby Rubovits, owned one of the largest printing companies in Chicago in the early 1900s. He published a few books himself as well. Rubovitz had high level social connections as well as business relationships in publishing, printing, retailing and manufacturing. He was likely responsible for the huge array of merchandise that was blessed with the image of Billiken.

With extensive connections in New York, a sales office was opened there. The announcement of the new offices shows the unique Billiken combination of “feel good philosophy” and hard sell. This from The Publishers Weekly of November, 1908:

“Billiken the “Good Luck God” has finally reached the East, and promises to add to the gayety of the nation if not in helping along business.

Billiken, the grinning little Japanese image, is the craze of the hour. His cult is spreading all over America. His worshippers are increasing every minute. He is a maker of happiness, a chaser of frowns. You must smile back at him. When you smile you are bound to feel in a good humor. When you are in a good humor everything seems brighter; you work with a better vim; you see the hopeful sides of things instead of the worst. He throws a spell over you that has the same effect as mental healing. You feel that you can do anything – and back of all achievement lies confidence. That is why Billiken brings luck. Billiken is not sold. He is loaned to you for a hundred years, at the rate of one cent a year, payable in advance. Billiken is made in a number of different sizes, who may or may not be seated on a throne. He was made by a girl in the Craftsman’s Guild in Chicago some months ago. Since then he has been reproduced and made thousands smile. Leading book and stationary houses have found him a trade bringer and many have exploited him in window displays to their advantage. He will attract custom and increase profits simply because that smile is contagious. Every man who sees it will want to purchase more or less goods. Consequently Billiken will be a factor in the development of prosperity. The image may be ordered from The Billiken Company at the Old Colony Building, Chicago, or from their Eastern agents, The Billiken Sales Co. 90 Centre Street, New York City.”[14]

The third executive of the company, James Rosenthal, was a partner in Rosenthal, Kurz & Hirschl, a leading Chicago law firm of the day. He likely spearheaded some of the litigation that embroiled Billiken in the early years. One of the most successful Billiken products was the 1909 E.I. Horsman doll that had a soft teddy bear body and a composite Billiken head. At one point, The Billiken Company sought an injunction against a competitor who was selling a similar doll called “Killiblues” that came complete with inspiring poetry, just like Billiken.[15]

In another case, The Billiken Company was denied a registered trademark on the word “Billiken” because the design had already been issued a patent and the name Billiken was already copyrighted. Therefore the trademark would have essentially extended protection indefinitely to an object that held a seven year design patent.[16] So perhaps, in the long run, the patent was not the best protection available as it only lasted until 1915, when the Billiken design officially entered the public domain.

It’s not known how much money Billiken generated for its owners over the years, but given his popularity it must have been substantial. Unfortunately, Florence Pretz felt cheated. She had agreed to license the rights to the Billiken patent for a paltry $30 per month.

Just eighteen months after Billiken’s first appearance in the newspaper, the headline in the Chicago Daily Tribune reads:

“Creator Casts Off Billiken.

Miss Florence Pretz Says Idol No Longer Brings Her Luck

Seeks Profit in Dollars

Chicago Manufacturers Reply Royalties Are Paid As Due”

The licensing arrangement described in the article is not very clear. Company attorney James Rosenthal states that The Billiken Company secured its rights from The Craftsman’s Guild and Edwin O. Grover, its head. He goes on the say that his company has promptly paid whatever considerations were due and that it’s been up to The Guild and Grover to pay Miss Pretz the royalty, which she admits was $30 a month.

Evidently seeing such success for Billiken and receiving such a small sum led Florence Pretz to become so bitter that, according to the article, she would rather “go out of her way than see a Billiken Throne, a Billiken pin, cuff buttons or anything else that is based on a Billiken model.” The article goes on to pose the question “Would you smash a Billiken if you had a chance?”- to which Miss Pretz replied “I certainly would.”[17]

But as you might expect from the woman who created the Billiken, Miss Pretz is described in the same article as being hard at work to originate another novelty product aimed to touch the fancy of the public in the same way Billiken did. Although she never accomplished that, at least we can hope that she had fun trying.

To close the discussion, rather than quote from the canon of Billiken’s hard-sell happiness philosophy, perhaps it would be more fitting to present the poem where Florence Pretz first met Billiken, as if in a dream. Maybe the next great god is still in here somewhere, among the Little People, just waiting to be patented. From the book More Songs from Vagabondia, here is the poem by Bliss Carman:

“Mr. Moon, a Song of the Little People”

O Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

Down on the hilltop,

Down in the glen,

Out in the clearin’,

To play with little men?

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

Hurry up your stumps!

Don’t you hear Bullfrog

Callin’ to his wife,

And old black Cricket

A-wheezin’ at his fife?

Hurry up your stumps,

And get on your pumps!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

Hurry up along!

The reeds in the current

Are whisperin’ slow;

The river’s a-wimplin’

To and fro.

Or you’ll miss the song!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

We’re all here!

Honey-bug, Thistledrift,

White-imp, Weird,

Wryface, Billiken,

Quidnunc, Queered;

We’re all here,

And the coast is clear!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

We’re the little men!

Dewlap, Pussymouse,

Ferntip, Freak,

Drink-again, Shambler,

Talkytalk, Squeak;

Three times ten

Of us little men!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

We’re all ready!

Tallenough, Squaretoes,

Amble, Tip,

Buddybud, Heigho,

Little black Pip;

We’re all ready,

And the wind walks steady!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

We’re thirty score;

Yellowbeard, Piper,

Lieabed, Toots,

Meadowbee, Moonboy,

Bully-in-boots;

Three times more

Than thirty score.

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

Keep your eye peeled;

Watch out to windward,

Or you’ll miss the fun,

Down by the acre

Where the wheat-waves run;

Keep your eye peeled

For the open field.

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

There’s not much time!

Hurry, if you’re comin’,

You lazy old bones!

You can sleep to-morrow

While the Buzbuz drones;

There’s not much time

Till the church bells chime.

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Mr. Moon,

Just see the clover!

Soon we’ll be going

Where the Gray Goose went

When all her money

Was spent, spent, spent!

Down through the clover,

When the revel’s over!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

O Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

Down where the Good Folk

Dance in a ring,

Down where the Little Folk

Sing?

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

References:

[1] The Canada West; Vol. 2 No. 1, May 1907

[2] The Canada West; Vol. 2 No. 3, July 1907

[3] The Canada West; Vol. 2 No. 4, August, 1907

[4] The Canada West; Vol. 2 No. 6, October, 1907

[5] Chicago Daily Tribune; May 3, 1908

[6] The Canada West; Vol. 4 No.3 July 1908

[7] St. Louis Post-Dispatch; November 1909

[8] Chicago Daily Tribune; February 14, 1912

[9] http://asp3.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/golden/grover.htm

[10] American Arts & Crafts from the Morse Collection. Object Guide Winter Park, FL 2009

[11] Chicago Daily Tribune; May 15, 1908

[12] Biennial Report by the Secretary of State to the Governor of Illinois, 1908

[13] The American Stationer; October 3, 1908

[14] The Publishers Weekly; November 23, 1908

[15] The Federal Reporter Vol. 174; page 830. 1910

[16] Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office; Vol. 143, June 1, 1909

[17] Chicago Daily Tribune; November 9, 1909