Billiken Lore

by Dorothy Jean Ray

Foreword

When I moved to Nome, Alaska in 1945 I became interested in a strange little ivory object called a billiken, which was sold by the hundreds—if not thousands—in the stores, or directly from the ivory carvers themselves. My curiosity as to their origin and history led to nothing. All that I learned—even from the old-timers—was that “it was something that the Eskimos always made.”

By the time that I had returned to Alaska for research in the ethnohistory and art of the Bering Strait Eskimos, I had discovered its origin, and although the billiken played only a tiny part of my research, I came to two important conclusions:

- that it was an object that the carvers hated most to carve,

- and that it was an important part of the Eskimo economy.

Robert Henning, publisher of the Alaska Sportsman, and collector of Native Alaskan crafts, and whose magazine featured many articles with subjects other than “sportsman,” suggested that I write what I had learned about the billiken for the magazine. I did, and that article appeared in the September 1960 issue.

That article created a new interest in the billiken, and over the years people sent me further information, and even billiken objects themselves. It had ballooned to the point where, by 1973, Henning, also publisher of the new Alaska Journal, and Robert N. DeArmond, its editor, suggested that I bring the billiken story up to date in the new journal. That greatly expanded version—the one included here—was published in the Winter 1974 issue.

Since then I have acquired more examples of the billiken journey, but they add only to “more of the same.” A few are still made of ivory, but the valuable walrus ivory is now put to a better use, and in 2005 there are more career options for the carvers.

The Billiken

(Originally published in The Alaska Journal, Winter 1974)

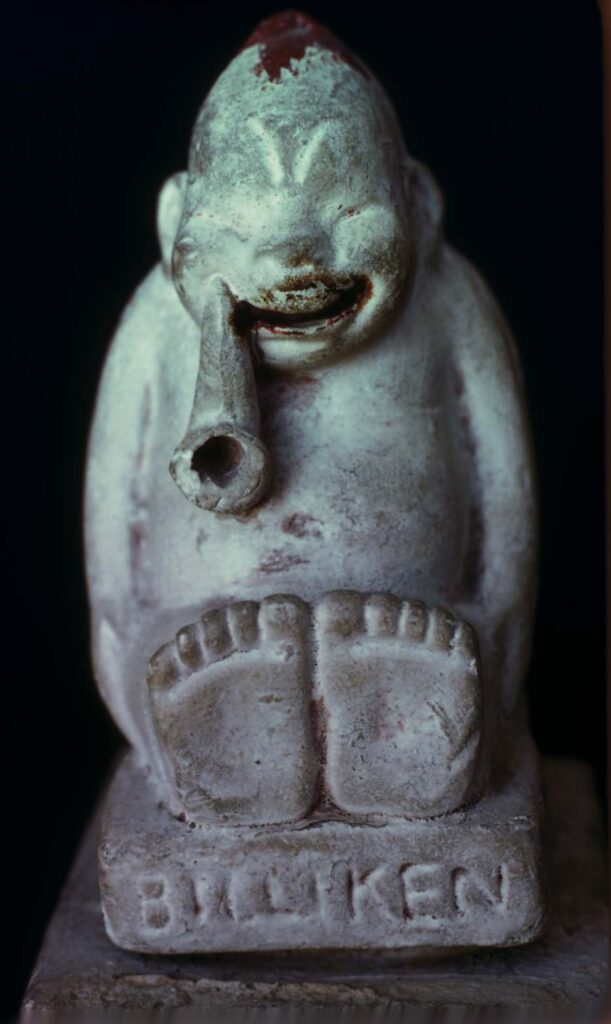

Along with the horseshoe, the rabbit’s foot, and the four-leaf clover, the billiken is one of America’s favorite good-luck pieces. Those who think it is only an Alaskan souvenir made by Eskimo carvers will be surprised to learn that it originated in Kansas City, Missouri—not Alaska—and that it is still being made in media other than ivory elsewhere in the world.

On October 6, 1908, Florence Pretz, an art teacher and illustrator, was given a seven-year patent for her “design for an image,” but the name “billiken” is not mentioned. Despite numerous inquiries, I have been unable to learn what it means or who named it. Possibly Miss Pretz left the naming up to the principal manufacturers of billiken objects, The Craftsman’s Guild and The Billiken Company of Chicago, and the Billiken Sales Co., the latter’s “Eastern Representative”, all of whom used the date and patent number of Miss Pretz’s invention on their objects.

I saw my first billiken in Nome in 1945, but no one could tell me its history or origin (“It’s something the Eskimos always made,” was a common remark) until 10 years later when my field work in contemporary ivory carving introduced me to Big Mike Kazingnuk, a Little Diomede Island man. Big Mike told me that his brother-in-law, Happy Jack, or Angokwazhuk, the famous ivory carver of Nome’s early days, had made the first ivory billiken in 1909 at the suggestion of a merchant who was called Kopturok (“Big Head”) by the Eskimos.

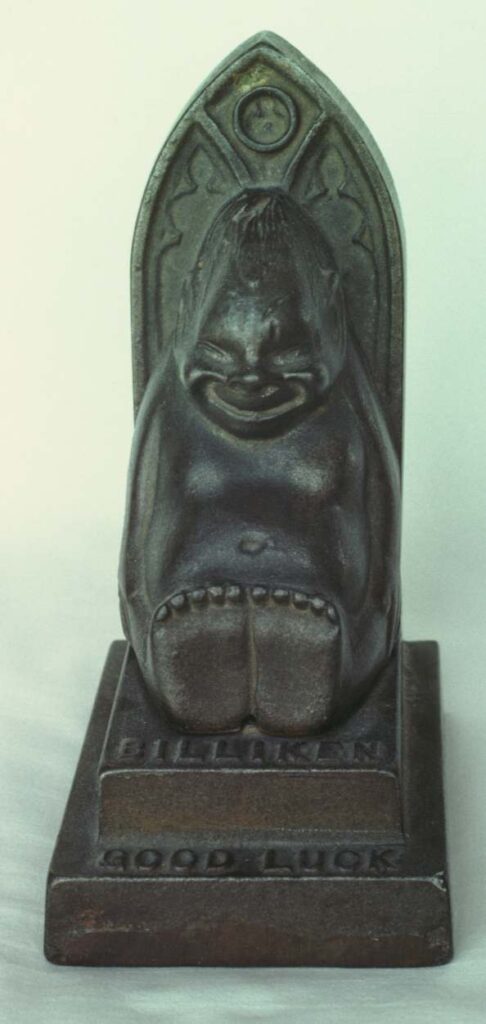

Happy Jack had copied it from a figurine brought from “the States” that summer. This information clearly established the fact that the billiken was not a traditional Eskimo object, but there remained the mystery of its origin. A trip to a Seattle antique shop only a few weeks later solved this final problem when I found one of the original figurines, a cast-iron bank. The number 39603 on the back of my discovery led to Miss Pretz’s patent and to her identity as the creator of the billiken.

My interest in the billiken had begun merely as an inquiry into one of the enduring and staple items of Eskimo ivory repertoire, but continued on as a fever of collecting original billikens and their later-day copies from the United States, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Japan, and of tracking down all available information I could about it. As I saw more and more billikens, it seemed remarkable that so many of the physical characteristics and meanings of the original invention had been retained over such a long time span and in so many media. Thus I set out to compile a history of this unique example of American folk superstition, although I must confess that I have never been overly fond of the billiken itself.1

Unlike Rose O’Neil, who designed the related kewpie figurine, Miss Pretz wrote nothing to my knowledge about the billiken, but she obviously had borrowed the shape from an Asian figure, possibly a Buddha or one of the many Taoist gods. However, her illustrations for children’s books include pixy-like figures similar to the “Brownies” that were invented by Palmer Cox in 1887, and these Brownie-like figures, which floated on oak leaves or nestled on downy tree trunks look very much like her own tour-de-force, the billiken.

THE ORIGINAL BILLIKENS

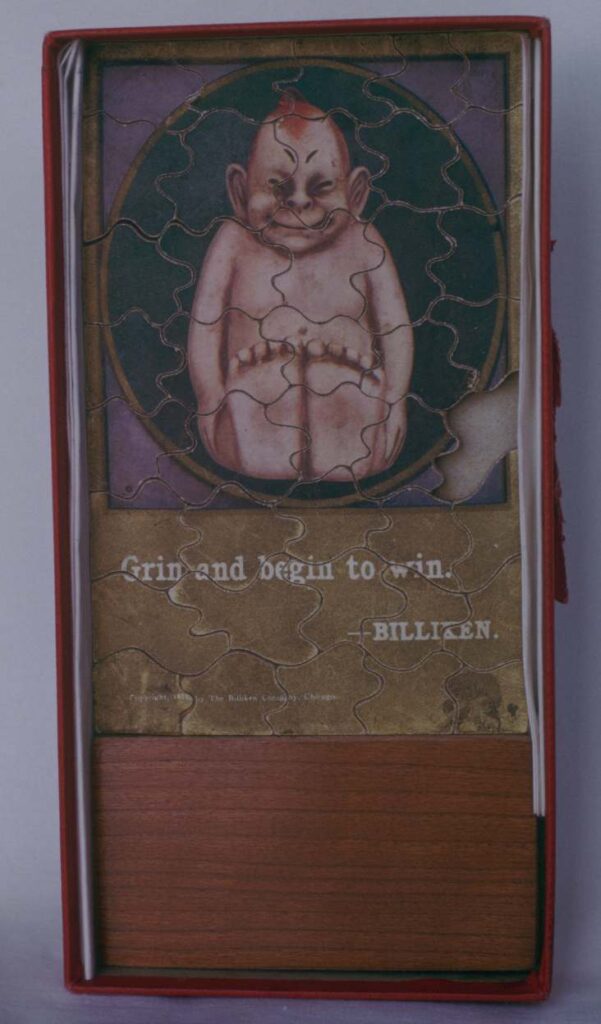

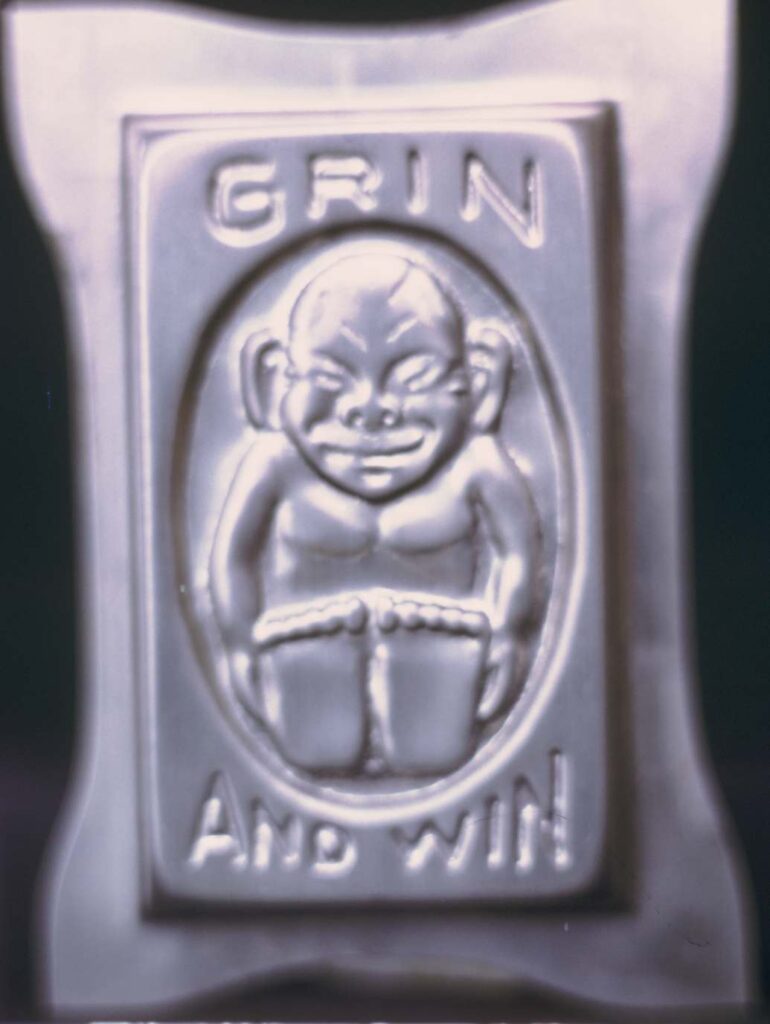

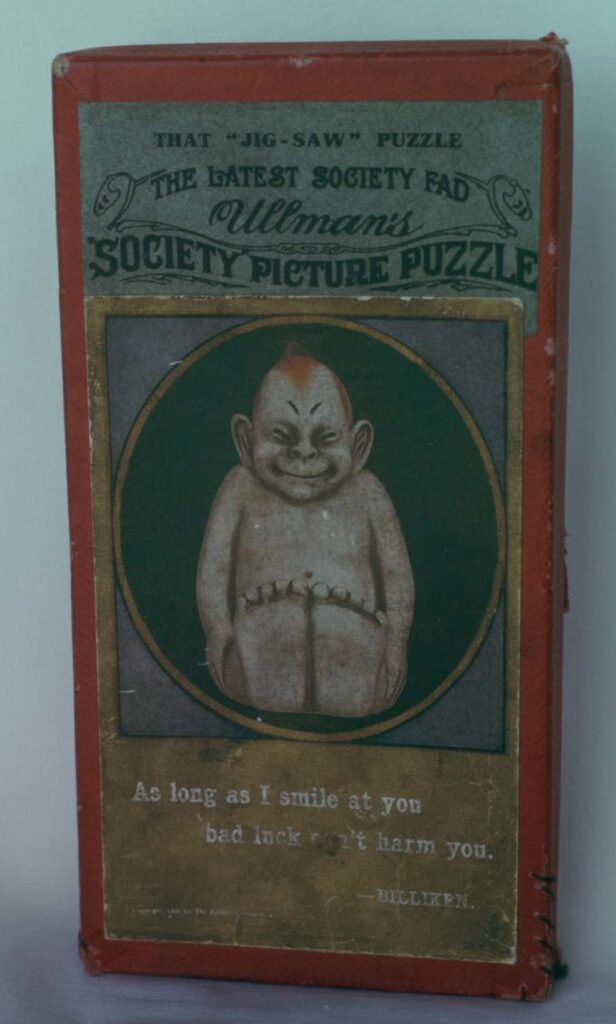

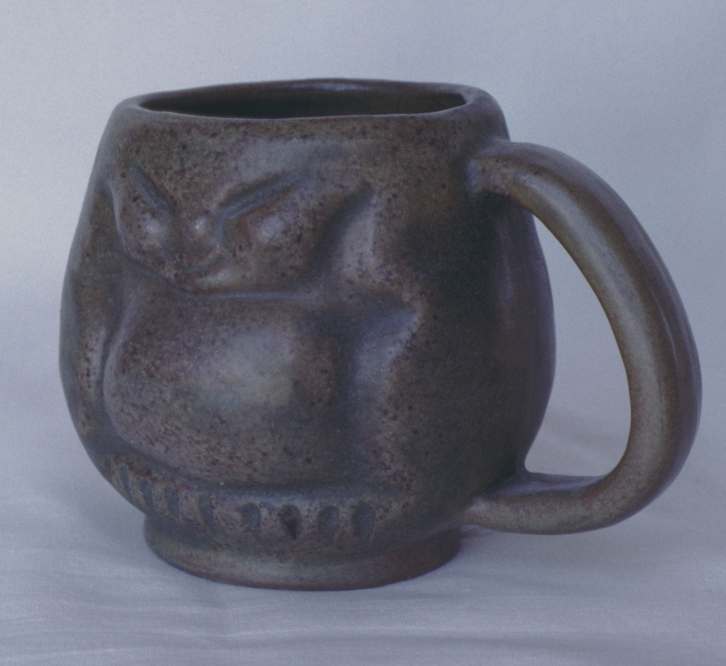

When Happy Jack made his first ivory billiken in 1909, the commercial ones were at the height of their success—having taken the country by storm—but by 1912 they had plunged to oblivion. Original billikens were made into a variety of forms: bisque dolls, clay incense burners, marshmallow candies, and cardboard jigsaw puzzles and postcards. There were metal banks, hatpins, watchfobs, and belt buckles, and glass bottles and salt and pepper shakers. A coin-like token had a billiken in the center with “Grin and Begin to Win” printed around the edge. Young women set plaster-of-paris or alabaster billikens on their dressers for good luck, and said, when things went wrong, “Don’t blame me, blame the billiken.” The billiken was celebrated in the songs, “The Billiken Man” and “Uncle Josh and the Billiken,” and dances with billiken dolls were performed on stage.

Other similar objects, like the kewpie doll, Gobbo, Silligan (“God of Laughter”), Joss, Billycan, and the subsequent “Billikant”, which flooded the market around that time, apparently were inspired by Miss Pretz’s billiken.

The kewpie was copyrighted by Rose O’Neil in 1909—a year after Miss Pretz’s billiken—and her kewpie trademark was not taken out until 1913. Miss O’Neil also designed a cheerful figurine that she called Buddha Ho-Ho.

Gobbo, a cherubic figurine with a tilting head, a huge smile and fat hands resting on fat knees, was made to be placed on an automobile radiator cap. An advertisement in The Scientific American for May 15, 1909, said, “THIS IS THE MASCOT that has brought good luck to the Maxwell during the entire 10,000 mile non-stop engine run. Attach one to your radiator cap and you will have no hoodoo.”

Silligan and Billycan apparently were names and objects changed merely enough not to infringe on the original copyright.

Joss was a seated figurine, skull cap on its head and a pigtail down its back, with hands clasping drawn-up knees. It was patented by the Florentine Alabaster Co. of Chicago the same year as the billiken, and one writer on dolls thinks that this figurine was the inspiration for the billiken, but it may have been the other way around.2 The name, Joss, was merely a pidgin English corruption of deos, the Portuguese word for god, and referred to Chinese gods and shrines in general.

Slogans and verses were distributed with the original billiken to advertise its magical qualities, thereby increasing its sales. These ads and verses suggested that placing faith in this man-made object could easily work wonderful changes in one’s life, but its poor record as a manipulator of destiny may have had something to do with its short life outside Alaska. Occasionally it has been suggested that the billiken performed the same function as the traditional Eskimo amulet, but the “luck” that was supposed to emanate from the possession and manipulation of the billiken was not at all comparable to the old Eskimo custom of wearing amulets, which were protective devices to keep away bad or undesirable spirits.

Slogans that were associated with the original billiken were “The God of Things as They Ought to Be” (a reinterpretation of Kipling’s L’Envoi: “Shall draw the Thing as he sees It for the God of Things as They Are!”); “Grin and Win”; and just plain “Good Luck.”

Some pretty bad verses were printed for distribution with both the original four-inch high, red-headed alabaster figurine and the soft-bodied doll with the billiken face. The leaflets containing these verses are now very rare, but I found some that had been pasted to old postcards, which, when steamed off told me considerably more about the advertising schemes for the billiken.

One of the leaflets has an eight-line poem on one side, and an explanation of the miraculous billiken on the other. This leaflet calls the billiken “The Good-Luck God” in addition to the “God of Things as They Ought to Be,” and its owner is instructed to “Tickle His Toes and See Him Smile.” The billiken was also billed as an amateur psychiatrist, as he was “A Sure Cure for [listed]: The Blues, That Solemn Feeling, The Grouch, The Hoodoo Germ, Hard-Luck Melancholia, The Down-and-Out Bacillus.” The recommended “dose” to make life rosy again was “One smile every ten minutes.”

Another leaflet, also with a poem on one side, declared in 1908 (when the billiken had scarcely begun its life) that “the country is ringing with stories of men and women who claim that Billiken has turned the tide for them and opened the way to wonderful strokes of fortune.” Furthermore, it gave the comforting information that “He throws a spell over you that has the same effect as mental healing. You feel that you can do anything—and back of all achievement lies confidence. That is why Billiken brings luck.” It further added that “Billiken is not sold. That would break his spell. He is loaned to you for 100 years for a hundred cents, paid in advance.”

The verses held promise of great expectations. One exploited a “happy” theme, and another, a “lucky” theme. The two verses were also used together as one poem:

I am the God of Happiness,

I simply make you smile,

I prove that life’s worth living

And that everything’s worth while;

I force the failure to his feet

And make the growler grin,

I am the God of Happiness,

My name is Billiken.

I am the God of Luckiness,

Observe my twinkling eye—

Success is sure to follow those

Who keep me closely by;

I make men fat and healthy

Who were quarrelsome and thin;

I am the God of Luckiness,

My name is Billiken.

One of the verses printed on the doll’s box also contained the familiar lucky theme, embodied, however, in even more forgettable poetry:

I’m Billiken whose lucky grin

Makes gloom run out and joy run in

I’m fond of little boys and girls

I love to nestle ‘gainst their curls

And so that it could be arranged

Into a doll myself I’ve changed.

The billiken doll has the earliest known patent on a complete doll (July 22, 1909) with a “Can’t Break ‘Em” head of a substance invented by Solomon Hoffman, and used on numerous dolls at that time.

Postcards (in addition to the pasted-up ones already mentioned) were printed with drawings of the billiken and with one or more of the various slogans or verses. A favorite couplet that was also used beneath the picture of a billiken on the box cover for a billiken jigsaw puzzle was:

As long as I smile at you

bad luck can’t harm you.

The Gobbo radiator cap was also advertised with information written in the form of a poem:

The smiling god of good fortune,

The original divinity of optimism,

Whose cheerful countenance

Brings good luck

And happy days to all who

Observe this rule of life:

“BE CHEERFUL AND YOU WILL BE RICH IN EVERYTHING.”

IVORY BILLIKENS

The first billikens in ivory were made to carry in the pocket or display on a table but they were later made into as great variety as the original billikens. I have seen billiken gavels, salt and pepper shakers, paper knives, pipes, cigar and cigarette holders, key rings, cocktail picks, handles for bottle openers, lariat ties, pendants, cuff links, earrings, zipper pulls, pickle forks, tie tacks, pawns in an ivory chess set, and links in necklaces, bracelets, and watch bands. They have also been made in bas relief on a number of objects like cribbage boards and napkin rings.

During World War II men stationed at Marks Field across the Snake River from Nome often commissioned carvers to carry out their ideas about souvenirs, among which were the milliken (a female billiken) and the “Billiken in a barrel.” The latter had a movable penis that popped out above the top of the barrel when the billiken, which was fastened to the barrel with a lacework of rubber bands, was raised.

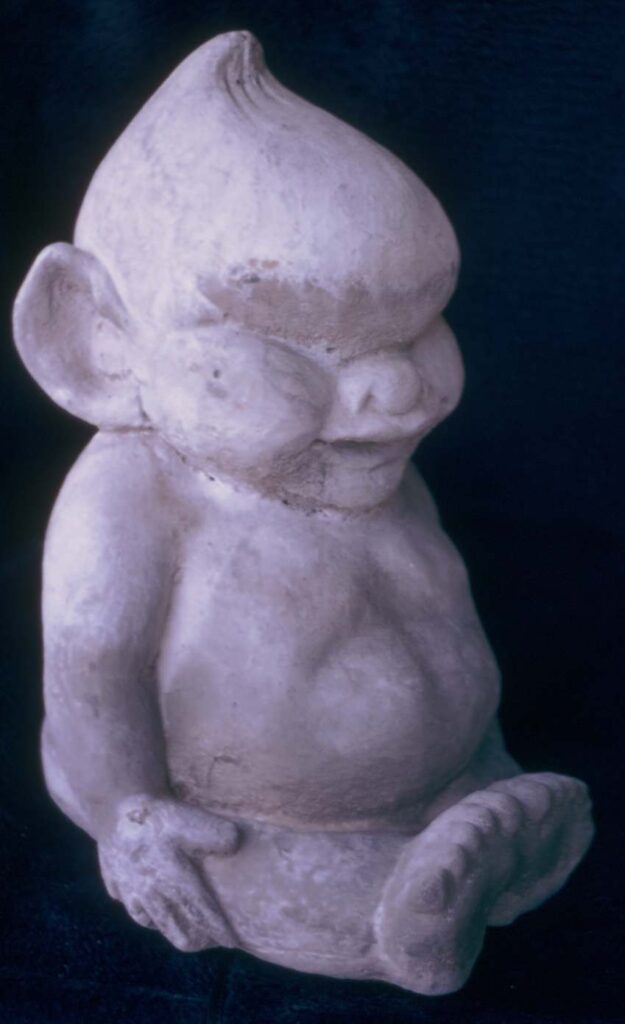

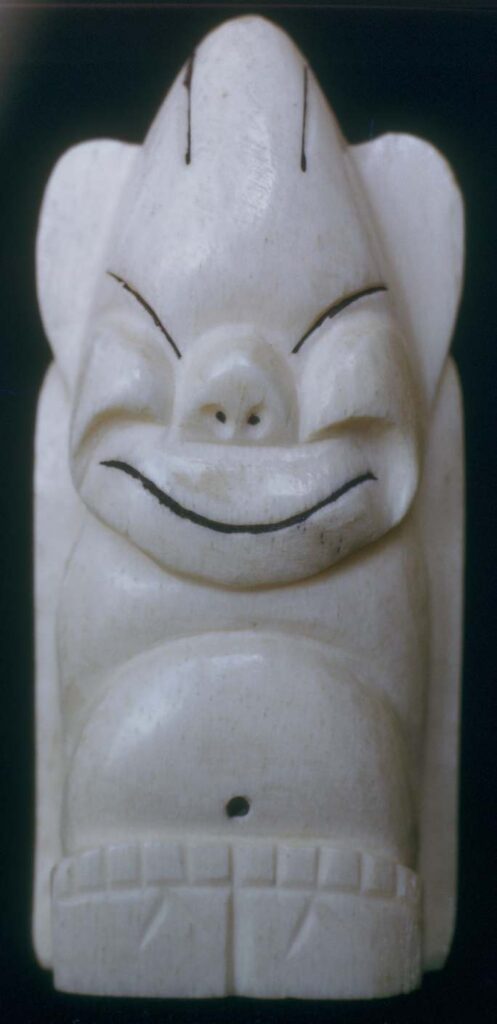

The diagnostic features of the original billiken have endured in ivory to this day: the grinning mouth, peaked hair, large eyes, jaunty eyebrows, hands plastered to the sides of the body, and feet stuck straight out in front. However, since Eskimos were unable to make the billikens in molds like the original ones, and had to carve within the limitations of walrus tusk ivory-and often in a hurry, they devised stylized gashes or dots for the fingers, toes, nostrils, eyebrows, mouth, nipples, and navel. These features were often colored with India ink. The head was pointed to represent the original peaked hair. These characteristics were retained for many years, no matter whether the billiken was big or tiny, fat or thin, until commercial carvers in Seattle began to make billikens from sperm whale teeth to send back to Alaska for sale. The pointed bent shape of the sperm whale tooth dictated a willowy creature without ears and with an elongated and peaked head. This style has recently been adopted by a few Alaskan carvers in walrus ivory. Another new, and quite different, interpretation of an ivory billiken, has extremely large ears and pronounced legs in a sitting position almost like the old Joss figurine. Other variations are constantly tried—like the milliken-billiken back to back and a billiken with a bright red tam-o-shanter—but few succeed. The carver finds that it is easier to carve the old-style billiken, which the tourists prefer anyway. The Canadian Eskimo’s success in soapstone sculpture after 1945 spurred carvers both in Alaska and Seattle to make billikens in stone.

Many of the old beliefs surrounding the billiken have continued to this day, although the popular Alaskan superstition of rubbing the billiken’s stomach while making a wish was not devised by the early writers of billiken slogans and verses, but was probably borrowed later from the beliefs of Oriental Buddha-like figurines that were made as gift and souvenir items, also to bring good luck and happiness. The most common is the hotei (or hoti) figurine, made as statues or jewelry. Hotei is a standing figure with a huge drooping stomach; its arms are upraised and it appears to be laughing uproariously. Advertisements for the hotei say that a person will have good fortune all day long if his belly is rubbed.

Popular good-luck pieces in Hawaiian gift shops are similar gods of “happiness” and “good-luck.” They are quite unlike the billiken in appearance, but the ideas connected with them are strikingly similar to those of the billiken today. Made of lava, the two most common are Hauoli Akua (Happy God) and Akaaka, also a “happy god.” Directions that accompany both of them say that happiness comes by rubbing the tummy.

A popular belief in Nome during the 1940’s and 1950’s was a reinterpretation of the original “loan” of the billiken for a hundred cents: an owner of a billiken will have small luck if he purchased one himself, but considerably more luck if he received one as a gift. However, if a person wanted superlative luck, a billiken had to be stolen. (At last report, I heard that this procedure had gone out of vogue.)

Alaskan storekeepers have devised many verses over the years for brochures to accompany the ivory billiken. A verse in the 1950 catalogue brochure of a Nome curio shop said:

Rub his tummy or tickle his toes,

You’ll have good luck so the story goes.

The same catalogue featured an erroneous story that the billiken had been copied after a big wooden billiken on Big Diomede Island. This publicity helped considerably to spread the false information that the billiken had been a traditional Eskimo object. The wooden statue referred to actually existed, but was a large driftwood stump carved into a face, which was fed a small amount of food whenever a person passed it so that its spirit would continue to provide good hunting.

FURTHER BORROWING OF THE BILLIKEN

The Alaskan Eskimo carver was not the only one to borrow the idea of the original billiken. At the height of its popularity it was also used as an emblem, trademark, and name by various enterprises, organizations, and publications. One of its earliest uses was as the patron saint for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle in 1909.

In 1910 or 1911, the name became attached to the St. Louis University athletic teams when a fan put a picture of a billiken in a campus hangout near the athletic field. Seeing a resemblance to the popular athletic director, John Bender, the public began calling the teams, “Bender’s Billikens.3

In 1910, an Ohio man named William I. Kin published a philatelic magazine, Billikins, the spelling with the ending -in resulting from the coincidence of his own name. This misspelling was deliberate, but others like “Chuck’s Billikin Gift shop” in Nome in the 1960’s; The Billikin ’49er, the official publication of the Billikin Chapter of the National Secretaries Association (Anchorage); and The Billikin Courier, an espionage novel of 1958 by T. C. Lewellen are unintentional misspellings.

In 1911, “The Royal Order of Jesters” was founded by a group of Shriners en route to a convention in Honolulu. They adopted the billiken as their symbol and the phrase, “Mirth is King” as their slogan. A Shriner must contribute many years’ work to their philanthropic programs to be invited into the Membership of the Jesters. By the 1960’s, the origin of their emblem had been forgotten, and one of its members, becoming curious, asked many members and wrote to numerous museums without finding information. Finally, he discovered my article in the Alaska Sportsman (September, 1960), and read the section about the figurine in my book Artists of the Tundra and the Sea. In 1968, he bound copies of his correspondence and information about the billiken into a report, which he presented to the Aloha Court in Honolulu for distribution to other courts.

The Jesters recently copyrighted the billiken, which members can purchase as gold-plated jewelry and statuettes, often with a crown on its head (i. e. “Mirth is King”) and green glass eyes and a red glass navel. 4

After a period of obscurity on the commercial market, the billiken gradually reappeared, and many of the revivals—especially the hideous ceramic statuettes, banks, and salt and pepper shakers made in Japan—were probably copied after the Alaskan ivory billiken. Many amateur sculptors have also tried their hand at making billikens in wood, clay, soap, and ivory, and commercial companies in Japan, Europe, and the United States are continuing the output in a variety of forms. Some of the recent ones illustrated in this article: beads, apparently made in Czechoslovakia just before World War II; the billiken-billikant figurines, which are very free interpretations of the originals; the concrete billiken bought in Richmond, Virginia in 1970; the tin mold, in Chicago in 1972; and the two sterling silver charms, purchased at the Seattle-Tacoma Airport in 1964 and 1973. I also have a gold-colored metal bank, which had been copied from the original by a Paris, Illinois, firm in 1973.

In 1920, a literary magazine, Billiken; revista illustrada, began publication in Caracas, Venezuela, with Lucas Manzano as editor, and continued until about 1946. Many whimsical billikens with arms and legs were drawn throughout the magazine in each issue.

In 1929, “Bud Billiken” became the “mythical saint” or godfather of black children when the Billiken Club for Chicago Children was founded. A parade and a picnic have been an annual event in August ever since. In 1968, 40 floats, 12 brass bands, eight drum and bugle corps, and 100 cars participated in the parade sponsored by the Chicago Defender Charities. A feature of the parade was marching on the newly-named Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.5

Over the years, other institutions and organizations have adopted the billiken name, such as the Billiken Lounge (Fairbanks), Billiken Ski Club (Seattle), and Billiken Theater (Anchorage). There are even children’s shoes called Billikens.

Probably the greatest heights to which a billiken has soared was as top man on a totem pole illustrated on the cover of a Bureau of Indian Affairs pamphlet, “Indians, Eskimos and Aleuts of Alaska” (1966). This combination of figures on a totem pole had also been reported in the April 1959 issue of the Alaska Sportsman as having been carved by one of its readers in New Hampshire. It is understandable why a nostalgic Alaskan might carve such a pole, but what right does a Missouri billiken have to be on a Tlingit Indian totem pole in a booklet that is supposed to contain authentic information about Alaskan Natives?

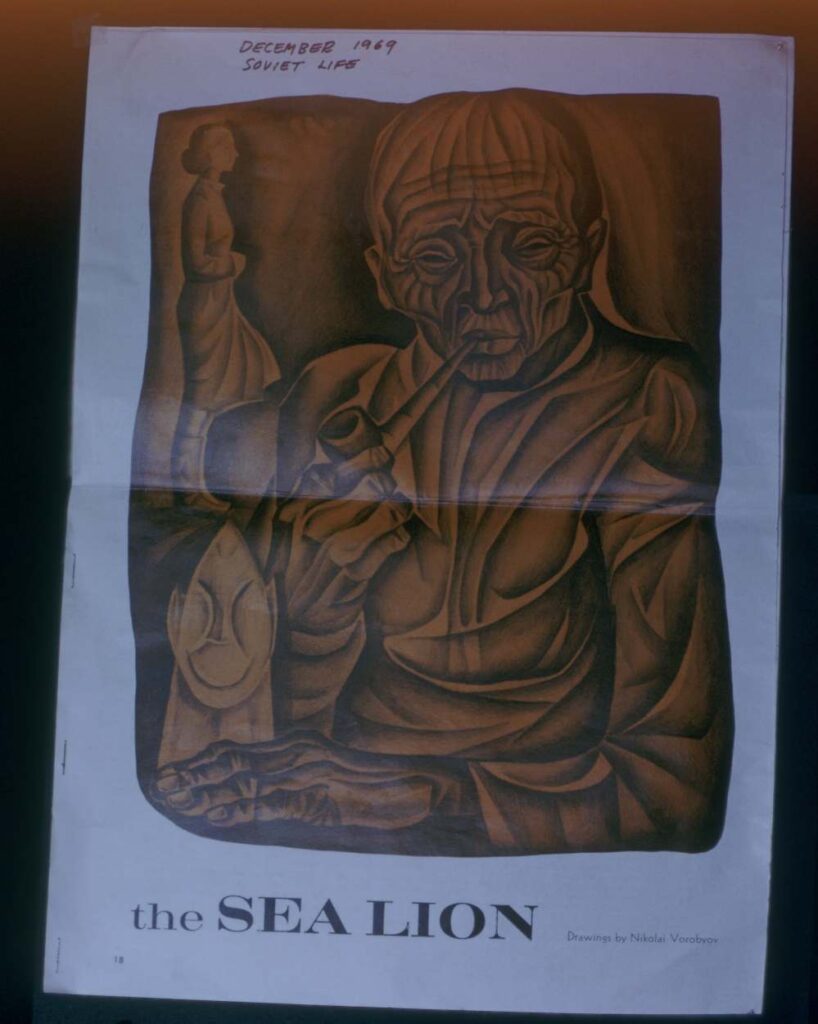

But this is scarcely less bizarre than the place of the billiken in the folklore of the Chukchi people of Siberia. In 1953, V. V. Antropova illustrated three ivory billikens in her monograph, “Survey of Chukchi and Eskimo Carving,” and in 1964, E. P. Orlova, four more in her book, Chukchi, Koryak, Eskimo, and Aleut Bone Carving.6 Called “pelikens” in Russian, these billikens look exactly like the Alaskan-carved ones, and well they might, because this figurine was introduced to the Eskimos of Uelen, Siberia, less than 40 miles from Little Diomede Island, by Alaskan Eskimos shortly after 1909. But I had not realized how firmly the billiken had become a part of the cosmic beliefs and carving repertoire of the Siberians until I read a short story, “The Sea Lion” by Yuri Rythkeu, a Chukchi writer born in Chukotka.7

The story concerns a young Chukchi girl, Emul, who, though offered a scholarship to a teachers college in Anadyr, had remained at home among her people, working as a waitress. Her father had been chairman of the local soviet, and her mother was head of a commission organized to abolish their old ways, but after World War II her father lost his job, and the people resisted the new ways and had returned to their old way of living.

When her grandfather died, Emul finished carving a number of ivory “idols” (billikens), which had already been paid for. This figurine, it is explained, was a very popular souvenir: a “fat little god with screwed-up eyes [that] stood on shelves and desks and . . . even clipped to the ears of fashionable women.” And, according to Chukchi mythology, this figurine originally had been used by every hunter who hung it on his hunting gear “so that everything bad in him would pass into the idol.” That was quite a responsibility for a billiken from Missouri.

One day a young archeologist asked Emul to make him a dozen “idols” to take back to Leningrad. “It will be something to remind me of Chukotka and you,” he said, ” . . . carve me something that will make me want to come back again.”

But his words, and something inside Emul prevented her from making the idol. Instead, she carved a sea lion—a rarity in that part of the country, but which she had once seen—with her whole mind and heart. When finished, it was a work of art like a walrus tusk engraved with beautiful scenes, which she had once found buried in her grandfather’s toolbox, quite unlike the boring, monotonous “idols.”

The young man was sorely disappointed when he got the sea lion instead of the billikens and asked Emul, “How will I be able to show my face in Leningrad without any?” Emul fled out to the tundra and to the cliffs of the sea as the ship prepared to take the young man and the sea lion away, but after her tears of bitterness had dried, she discovered that the gift of seeing things in their true perspective had been restored to her, and so she went home, renewed.

This story, too, puts the billiken in its proper Alaskan perspective, because of all objects made by the Eskimo carver, few present less of a challenge to make, except possibly how best to use small bits of ivory. Despite the contemporary carver’s reluctance to try innovations—mainly because of economic reasons—carving the billiken is regarded only as a necessity to make ends meet. The billiken is really a caricature of the carver himself, but to the tourist, few souvenirs so readily connote “Alaska” even though it is a cartoon.

Notes

[1]I am especially indebted to Gloria F. Huntington of Seattle for finding many of the billikens in my collection, and to Robert Elder, Jr. of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. for putting his information about billikens at my disposal. Others who have given me billikens or data for this project are Susan and Henry D. Barrow, Dale and Robert De Armond, Margaret Lantis, Myles Libhart, Patti Lipman, Leonard F. Porter, Verne F. Ray, Jane Schuldberg, Rachel Simmet, and Ramona Weeks.

All billikens illustrated are from my collection, and all photographs are by my late husband Verne F. Ray, unless otherwise stated.

[2]Clara H. Fawcett, “Billiken Dolls and Other Dolls of 1907-12,”Hobbies, May 1962, p. 39.

[3] Information from Father Francis J. Yealy, S. J., St. Louis University.

[4] Information from Carnie A. Generaux, Rancho Santa Fe, California.

[5] Chicago Sun-Times, 11 August 1968.

[6] V. V. Antropova, “Sovremennaia chukotskaia i eskimosskaia reznaia kost.” Sbomik Muzeia Antropologii i Etnografii, vol. 15, 1953, plate 20; E.P. Orlova, Chukotskaia, Koriakskaia, Eskimosskaia, Aleutskaia reznaia kost. Akademiia Nauk, SSSR, Novosibirsk, 1964, plate 50.

[7] Soviet Life, December 1969, pp. 19-21, 58.

About the author:

Dorothy Jean Ray was an anthropologist whose Alaskan research has resulted in many books and professional papers, including The Eskimos of Bering Strait, 1650-1898; Eskimo Art: Tradition and Innovation in North Alaska; Artists of the Tundra and the Sea; Eskimo Masks: Art and Ceremony; Aleut and Eskimo Art; and Legacy of Arctic Art.

She has also written for Alaska History, Alaska Journal, Alaska magazine, American Indian Art, Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, Arctic Anthropology, The Beaver, Journal of the West, Names, Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Polar Notes, and others.

She received an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from her alma mater, University of Northern Iowa.

–Verbeck Smith

Note – Dorothy Jean Ray died December 12, 2007 in Port Townsend, Washington.

Copyright 1974, 2005, 2008 by Dorothy Jean Ray

Originally published in The Alaska Journal, (Winter 1974), pp. 25-31.

Copied and published in this form in 2008 by kind permission of the author’s son and heir, Eric Thompson.

Additional material copyright 2005 by Verbeck Smith. Used here by kind permission of the author.

Special thanks to Verbeck Smith and Neil Smith for making the contents of billikenlore.com available to the Church of Good Luck